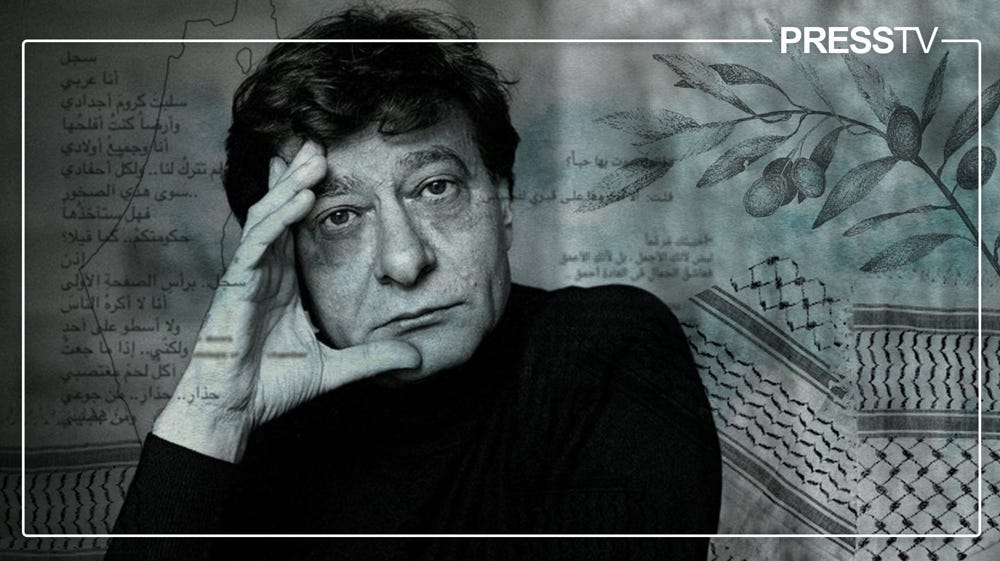

Mahmoud Darwish: Olive Trees, Exile, and the Poetry of Return

From a razed village to a global conscience, the Palestinian poet turned memory into resistance

Before Mahmoud Darwish’s name traveled the world in dozens of languages, he was a child from al-Birwah, a Palestinian village wiped from the map in 1948. His family fled to Lebanon, returned to find their home demolished, and resettled in Deir al-Asad as “internal refugees” after missing Israel’s census. That early rupture—uprooting, dispossession, life under military rule—honed a voice that would entwine the fate of a people with the endurance of a landscape.

A line from Darwish’s poetry expresses this inseparability:

“If one day I return,

Take me as a veil to your eyelashes

Clothe my bones with grass.”

Darwish began writing as a schoolboy, acutely aware of how occupation reordered childhood into permits, checkpoints, and absence. His verses quickly drew official ire; a military governor warned him to stop. Arrests and house arrests followed from his teens, yet his poetry only broadened its audience, becoming a common tongue for grief, steadfastness, and the Palestinian insistence on life.

In the 1960s, Darwish’s style turned spare and direct, a populist cadence that traveled easily from page to rally. “Identity Card,” collected in Awraq al-zaytun (Leaves of the Olive Tree, 1964), became both protest and affirmation—the voice of a man reduced to a number insisting on dignity. Speaking in the first person, he opens and builds insistently:

“Write down

I am an Arab

My I.D. card number is 50,000

My children are eight in number

The ninth arrives next summer.

Does this bother you?”

Exile reshaped his poetics after 1970, when he was barred from returning home while studying in Moscow. He lived mostly in Beirut and Paris, writing with richer metaphor and symbol. Palestine, in his lines, was mother and beloved, earth and promise; olive trees, thyme, and stone became emblems of a people’s rootedness. Critics often note how he transformed trauma into cultural resistance, making poetry a repository of memory against erasure.

“These lines evoke the persistence of hope amidst violence:

“Streets encircle us

As we walk among the bombs.

Are you used to death?

I am used to life and to endless desire,”

This fusion of land and identity—sometimes described as “eco-resistance”—runs through his work. Nature isn’t scenery; it is witness and kin. The olive grove, the herb sprig, the rock ledge, all carry history and refuse oblivion. That ethic resonated far beyond Palestine, earning Darwish international recognition, including the Lannan Cultural Freedom Prize, the Lenin Peace Prize, and France’s Belles-Lettres Medal. Marking five decades of occupation, he affirmed that Palestinians would not surrender their own narrative or their bond to place.

He died in 2008 at 67, after heart surgery, leaving a body of work that still furnishes language for dignity, longing, and return. Through his enduring verses, the Palestinian struggle remains alive, reminding the world of the quest for justice, identity, and freedom.

Reference: PressTv