Two Minds, One Horizon

Exploring the Convergent Paths of Ibn Arabi and Allameh Tabataba'i on Reality, Humanity, and the Divine

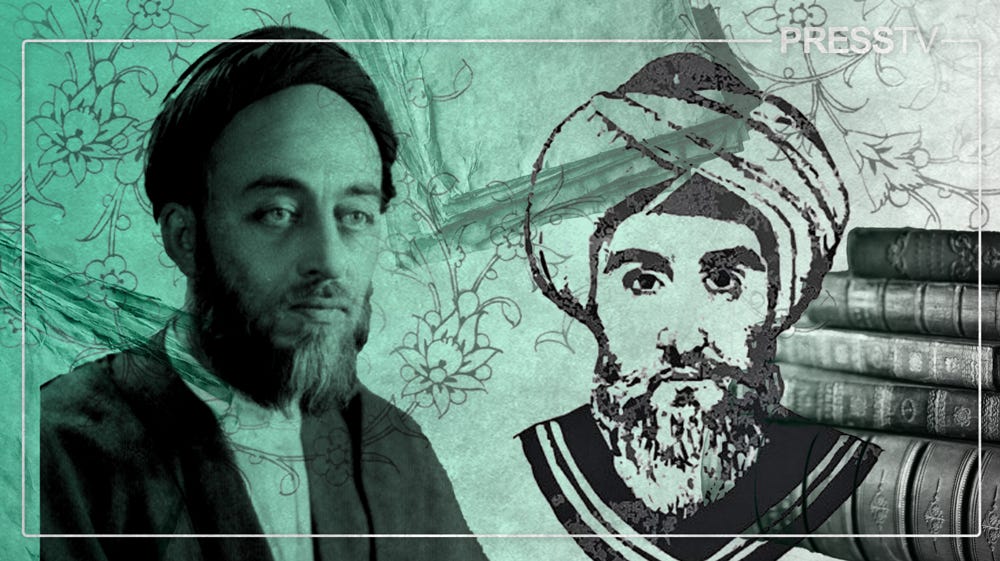

An Unlikely Pairing

At first glance, Muḥyi al-Din Ibn Arabi and Allameh Sayyid Muḥammad Ḥusayn Ṭabaṭaba’i appear to be intellectual worlds apart. Separated by eight centuries, geography, and temperament, one was a wandering Andalusian mystic of the 12th century, the other a reserved Iranian philosopher-exegete of the 20th.

Ibn Arabi’s language was famously symbolic, dense, and coded, earning him a reputation for unveiling profound secrets by some and for destabilizing theological boundaries by others. Allameh Tabataba’i, in contrast, was a master of clarity, whose life’s work was to rebuild a coherent Islamic intellectual tradition by fusing meticulous textual analysis with philosophical reason.

Yet, despite these differences in style and era, they stand as two points on the same continuous arc. Both dedicated their lives to the same monumental quest: to understand the intricate relationship between the Divine, the cosmos, and the human being.

The Mystic’s Vision: Ibn Arabi

Born in 1165 in Andalusia, Ibn Arabi’s life was one of travel, writing, and profound spiritual immersion. His seminal works, such as al-Fuṣuṣ al-Ḥikam (The Bezels of Wisdom) and al-Fatuḥat al-Makkiyyah (The Meccan Revelations), redefined the vocabulary of Islamic spirituality.

His philosophy is often associated with wahdat al-wujūd (the unity of existence). For Ibn Arabi, creation was not a separate act but a perpetual reflection—a vast mirror through which the singular, infinite Divine reveals its own Names and attributes. He argued that the “Perfect Human” is the pinnacle of this reflection, the one being in whom all Divine Names are gathered most completely. This “Perfect Human” acts as the very channel through which God’s grace flows to the cosmos.

Ibn Arabi’s approach was holistic, insisting that self-knowledge is inseparable from knowledge of God. To understand oneself was to understand the divine imprint within.

The Philosopher’s Method: Allameh Tabataba’i

Allameh Tabataba’i was born in 1903 in Tabriz, Iran, into an age of intense secular pressure and intellectual fragmentation. Settling in the quiet city of Qom, he took on the immense task of grounding Islamic thought for the modern world.

His 20-volume commentary, al-Mīzān fī Tafsīr al-Qur’ān (The Balance in the Interpretation of the Quran), is a masterpiece of this effort. In it, he masterfully wove together textual fidelity, philosophical rigor, and spiritual intuition. Rather than relying on symbolic prose, Allameh Tabataba’i used rational argument and Qur’anic exegesis to arrive at complementary insights.

While he didn’t use the exact same terminology, his concept of the Wali of God or Al-Mukhlasin (the “Perfected One”) resonates deeply with Ibn Arabi’s “Perfect Human.” For Tabataba’i, this is the individual who, through spiritual perfection, fully reflects God’s Names and thus becomes a locus of divine guardianship on Earth.

A Common Horizon

The bridge connecting these two great minds is their shared conviction. Both believed that the universe is not a random assortment of objects but a carefully structured, meaningful expression of Divine Names. Both saw the human being as the central-most point of this expression, uniquely designed to perceive and manifest it.

On the Divine: Both saw God not as a distant, abstract creator but as an intimate, ever-present reality permeating all of existence.

On Humanity: Both saw the human being as a microcosm, a complete map of the cosmos, holding the potential to be a perfect mirror for the Divine.

On Knowledge: Both understood that true understanding requires more than just one faculty. Ibn Arabi’s mysticism and Tabataba’i’s philosophy are, at their core, calls to integrate the intellect and the heart, rational inquiry and spiritual experience.

Though their methods were different—one using the coded language of mystical unveiling, the other the precise language of philosophical exegesis—they were both pointing to the same truth. They teach that the world is saturated with meaning, and the human purpose is, ultimately, to learn how to see it.

Reference: PressTv